The word slogan, as in advertising slogan, is an ancient Irish word. Once upon a very long time ago, noble Gaelic warriors would muster for battle on some misty moor. The two armies would face each other, draw their ancient swords, and charge, whilst shouting over and over again their army-cry or slua-gairm.

This slua-gairm could be the name of the clan, or some sort of motto. It became customary for nobles and chieftains to put this motto on their coat of arms, and so, in heraldry, those words written on the ribbony thing under the shield became known as the slogan. From there the word started to mean the motto of any particular group, usually political. And from there it got dragged off into the world of advertising, where it has become debased and familiar. But once you know this history, and know this origin, you can still imagine those ancient warriors charging bravely to their deaths shouting again and again “Should’ve gone to Specsavers! Should’ve gone to Specsavers!”

To read the rest of the story, click on this article in the The Irish Times while I listen to Mark Forsyth who was given a copy of the Oxford English Dictionary as a christening present and has never looked back. Here he is again, sharing his heaps of useless information with a verbose world:

There are formulas for great poetry, advertising, and great political speeches, and they are formulas you can learn. The Ancient Greeks worked them out. Shakespeare learned them in school. Today they are forgotten, but, when people stumble across them, a great line is born. Mark is a journalist, proofreader, ghostwriter, and pedant, but here, he delves into how these “formulas” for writing can change our everyday life and can take you anywhere.

In this hugely entertaining talk he takes on what is considered 'correct' English: dispelling myths, highlighting inconsistencies and generally poking fun at what all our teachers taught us to be true. From prepositions to plurals he goes to the far reaches of the archives to tease out the most ridiculous rules that apparently govern our language, silencing even the most punctilious of linguistic pedants!

Mark Forsyth adjucates Caul(dron) My Bluff panel game at the Cauldron, 24th June 2013. On the bluff panel are Ben Cottam, Kevin Jackson and Rob Stott. Compere: John Farndon

Most politicians choose their words carefully, to shape the reality they hope to create. But does it work? Here Mark Forsyth shares a few entertaining word-origin stories from British and American history (for instance, did you ever wonder how George Washington became "president"?) and draws a surprising conclusion.

“Bond, James Bond.” It’s one of the most famous lines in movie history, first spoken by Sean Connery as double agent JamesBond in 1962’s Dr No. But how did it become so? It’s all thanks to a literary device called Diacope, as Mark Forsyth explains.

In this second part of the series on language in cinema, he examines the various uses and meanings of rhetorical questions in the movies, from PulpFiction to DirtyHarry.

Here Mark explains how a common figure of speech has inspired some famous lines of dialogue in movie history, from The Treasure of the Sierra Madre to The Breakfast Club.

Being so close to Christmas, here is Mark's essential guide to your festive libations, drinking etymologically significant cocktails so you don't have to. No authors were harmed (too much) in the making of this film. More in Mark's "A Short History of Drunkenness"

Here are his final words on the origins of Christmas words - tangerine, walnut, and turkey, and what exactly a Yule hole is - all of which is revealed in "A Christmas Cornucopia"

And there's lots more on English Verse , as well as Mark Forsyth's own blog "Inky Fool" as well as his facebook page, although, as he said,

"Only in the bookshop, in the Good Bookshop, can you stumble across the book that you never knew you wanted, that will answer all the questions that you never knew to ask. It is there, waiting, but you cannot find it by searching. You must find it by chance. Somewhere on the shelf at the back, over to the right." And I keep looking ...

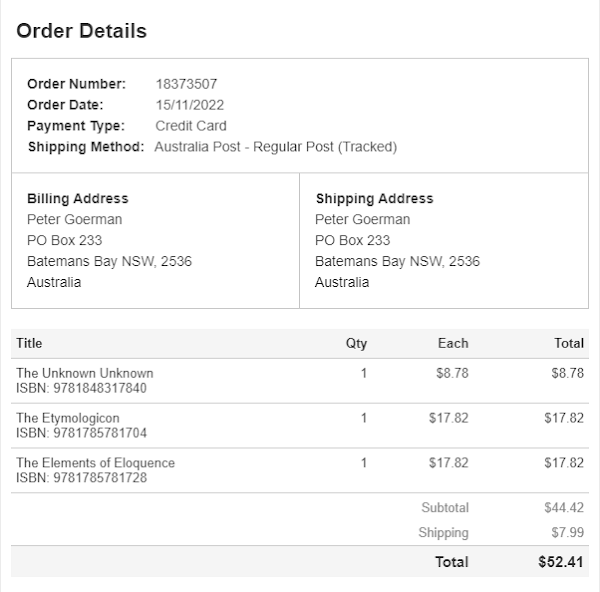

P.S. Of course, I have since ordered another three of his books. For more information about his books, click here.

(I could've bought this set for a mere 11 pounds but I discovered it too late - click here)