The very thought of going back to Lower Binfield had done me good already. You know the feeling I had. Coming up for air! Like the big sea-turtles when they come paddling up to the surface, stick their noses out and fill their lungs with a great gulp before they sink down again among the seaweed and the octopuses. We're all stifling at the bottom of a dustbin, but I'd found the way to the top. Back to Lower Binfield!"

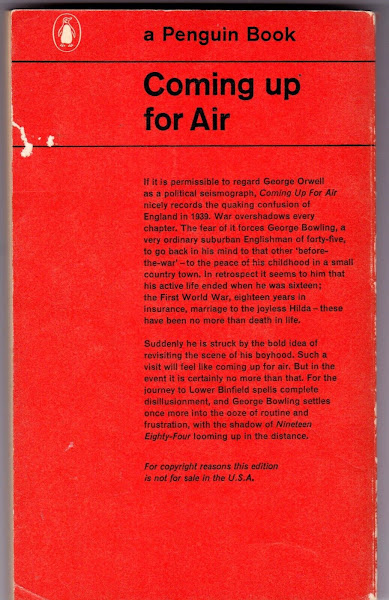

I didn't quite know what to expect when I bought George Orwell's "Coming Up for Air". I knew it wouldn't be a scathing allegory like "Animal Farm" and I knew it wouldn't be as terrifying as "1984"; what I didn't know was that this is a rather bleak comic novel, written and set in 1938/1939, which follows George Bowling, a 45-year-old husband, father, and insurance salesman, who foresees World War II and attempts to recapture idyllic childhood innocence and escape his dreary life by returning to Lower Binfield, his birthplace. It's not a high-octane, a thrill-a-minute book. In fact, very little happens, but it is an enjoyable read, in a 'nothing-much-happens' kind of way. The first line says it all, "The idea really came to me the day I got my new false teeth."

Its anti-climatic ending, its mundanity reflects the return by the two Georges to their dull existences – Bowling back to his suburban life in London and Orwell back to his from Marrakech where he wrote the book. If mundane endings are good enough for Orwell, they are good enough for me.

"The past is a curious thing. It’s with you all the time. I suppose an hour never passes without your thinking of things that happened ten or twenty years ago, and yet most of the time it’s got no reality, it’s just a set of facts that you’ve learned, like a lot of stuff in a history book. Then some chance sight or sound or smell, especially smell, sets you going, and the past doesn’t merely come back to you, you’re actually IN the past. It was like that at this moment."

"We say that a man's dead when his heart stops and not before. It seems a bit arbitrary. After all, parts of your body don't stop working - air goes on growing for years, for instance. Perhaps a man really dies when his brain stops, when he loses the power to take in a new idea. Old Porteous I like that. Wonderfully learned, wonderfully good taste - but he's not capable of change. Just says that same things and thinks the same thoughts over and over again. There are a lot of people like that. Dead minds, stopped inside. Just keep moving backwards and forwards on the same little track, getting fainter all the time, like ghosts."

"They don’t want to have a good time, they merely want to slump into middle age as quickly as possible. After the frightful battle of getting her man to the altar, the woman kind of relaxes, and all her youth, looks, energy, and joy of life just vanish overnight. It was like that with Hilda. Here was this pretty, delicate girl, who’d seemed to me—and in fact when I first knew her she was—a finer type of animal than myself, and within only about three years she’d settled down into a depressed, lifeless, middle-aged frump."

"As a boy, it occurred to me, all people over 40 had seemed to me just worn-out old wrecks, so old that there was hardly any difference between them. A man of 45 had seemed to me older than this old dodderer of 65 seemed now. I was 45 myself. It frightened me."

"A rose smells the same to me now as it did when I was twenty. Ah, but do I smell the same to the rose?"

It's the kind of nostalgic book you read on a cold and rainy day like today and when you've reached a certain age like I have. I enjoyed reading this little-known novel which is just as well since it cost me over $20 on ebay; however, you can read it for free on www.archive.org.